A Short History of the Canadian Military Police

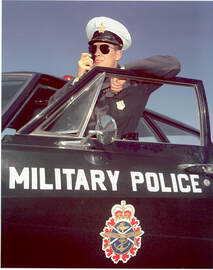

Although provost and military police capabilities existed in Canada well before Confederation in 1867, it was not until 1917 that the first Canada-wide military police organization was formed. Throughout the last century, the Royal Canadian Navy, Canadian Army, Royal Canadian Air Force and unified Canadian Armed Forces have all maintained military policing capabilities to varying degrees.

This year, the Military Police Branch of the Canadian Armed Forces celebrates its 84th anniversary. The Branch traces its unbroken lineage back to the creation of the Canadian Provost Corps on 15 June 1940, which has been adopted as its official birth date.

What follows is a short history of military policing in Canada.

Canadian Militia and Canadian Army

In colonial Canada, provost marshals and military police are known to have enforced military discipline over regular and militia troops in garrison towns and during military campaigns. In 1677, during the French colonial period, a small Maréchaussée (military constabulary) commanded by a an officer titled Prévôt des maréchaux (Provost of the marshals) was established in Québec City. Created by a royal edict from Louix XIV, it exercised jurisdiction over soldiers as well as the civilian population. A Maréchaussée detachment was also established in Montréal for a short period beginning in 1709. Following the Conquest of 1760, authorities in British North America initially used the Provost Marshal title in both civilian and military contexts. However, the civil Provost Marshal posts in the Canadian colonies were eventually replaced by Sheriffs.

|

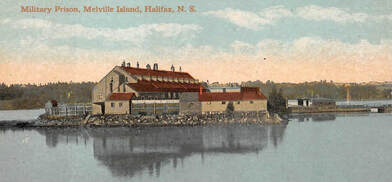

During the War of 1812, Cornet* Amos McKenney, an officer of the Niagara Light Dragoons (later named the Troop of Provincial Dragoons), acted as Provost Marshal for the Militia of Upper Canada—perhaps being the first non-Imperial officer to carry out such duties in Canada. From 1812 to 1822 the British garrisons at Québec city and Halifax each had a Deputy Provost Marshal, and by the early 1860s Garrison Military Police (GMP) organizations were operating in Kingston, London, Montréal, Québec and Halifax.

After Confederation in 1867, Canadian Militia documents speak of the requirement for units to appoint Provost Sergeants, regimental police and camp police. Militia documents from the 1880s further recommended the appointment of Provost Officers to supervise camp police at large militia training concentrations—a practice that was also reported on by period newspapers.

|

* Cornet is an archaic officer rank equivalent to Second Lieutenant. Amos McKenney was commissioned from the ranks during the war, having previously served as a Sergeant.

|

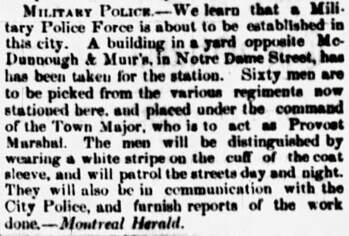

The first all-Canadian Garrison Military Police organization was likely that which operated from the Fortress of Halifax (the Citadel). The British turned this fortress over to the Canadian Department of Militia and Defence in 1906, and Fortress Standing Orders from 1908 show that a GMP force of one sergeant, three corporals and 13 men (all from the Permanent Force of the Canadian Militia) were operating in Halifax to help maintain good order and discipline. A district military prison—with its own superintendent, chief warder and five NCO assistant warders—was also operating at nearby Melville Island.

|

Canada entered the First World War without a nationwide military policing organization. In the years immediately preceding the war, Camp Provost Marshal appointments had become the norm at training venues and most regiments were appointing local personnel to act in unit policing roles under the direction of a Provost Sergeant. Starting in August 1914, each of the ten numbered Military Districts gradually began forming Garrison or District Military Police organizations under the direction of an Assistant Provost Marshal (APM)—sometimes assisted by a Deputy Assistant Provost Marshal (DAPM)—to more effectively conduct military policing activities outside of individual unit lines. Early in the war some APMs were involved in arresting and interring "enemy aliens" living in Canada (under the legal authority of the War Measures Act), but MP involvement in this activity tapered off significantly after 1916.

In France and Belgium, the Canadian Expeditionary Force also quickly adopted the British practice of appointing APMs to coordinate military police activities and a substantial number of troops were transferred under the Canadian Division and Corps APMs to act as a dedicated MP force. This included former cavalrymen who were employed as Military Mounted Police (MMP) to allow for the necessary level of mobility. In support of large operations, the divisional APMs would frequently employ augmentees from combat units to assist their MP and MMP cadres in conducting traffic control duties, manning battle straggler posts and controlling Prisoners of War.

In England, beginning in 1915, APMs and detachments of Canadian Military Police (CMP) were established in London, Shorncliffe, Bramshott and several other locations with large concentrations of Canadian troops. On 3 April 1918, under the authority of Headquarters Canadians Routine Order No. 3780, all Canadian Military Police in England and France were formed into a single organization called the Corps of Canadian Military Police (Corps of CMP) with an establishment of 484 non-commissioned members. The officers (APMs and DAPMs) were seconded from their parent units and were not counted against those numbers. Effective 20 August 1918, the establishment was reduced in England and increased in France for a new total of 472 non-commissioned troops. The Corps of CMP fell under the authority of the Minister for Overseas Military Forces of Canada, based in England, and as such was completely separate and distinct from the military police operating in Canada who fell under the Minister of Militia and Defence.

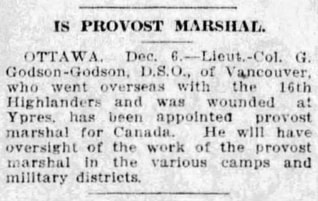

(Source: Vancouver Sun, Sunday 7 Dec 1917, pg. 1)

(Source: Vancouver Sun, Sunday 7 Dec 1917, pg. 1)

The publication of Militia General Orders No. 93 and 94 on 15 September 1917 marked a turning point for military policing back in Canada. These orders formalized the various GMP organizations into a new entity called Military Police, Canadian Expeditionary Force (MP CEF), with numbered detachments for each of the ten Military Districts across the country. This was followed on 4 December 1917 with the appointment of Colonel Gilbert Godson-Godson as Provost Marshal for the Dominion of Canada with the authority to oversee the work of all APMs in charge of these MP CEF detachments. On 22 March 1918, the government passed Order-in-Council 1918-0722 which directed that all MP CEF detachments be formed into a new organization called the Canadian Military Police Corps (CMPC). This reorganization was formalized in General Order No. 47 (1 April 1918) which set the initial CMPC establishment at 30 officers, 238 non-commissioned officers and 582 lance corporals for a total of 850. Thirty-four horses were also authorized to provide a limited mounted capability. All non-commissioned members of the Corps were entitled to "extra duty pay" for carrying out police duties. The CMPC was by then very involved in enforcing the Military Service Act (MSA)—apprehending draft evaders and deserters—and in May 1918 the government approved a transfer to the Department of Militia and Defence of a special branch of the Dominion Police that had earlier been formed to conduct similar duties. This merger was further formalized in CEF Routine Order No. 815 (17 July 1918) which created two branches of the CMPC: the Civil Branch (comprising the aforementioned Dominion Policemen in plain clothes); and the Military Branch (comprising the uniformed military members). As Provost Marshal, Colonel Godson-Godson retained full control of both branches of the CMPC. The special Dominion Policemen engaged in MSA enforcement were transferred back under the control of the Department of Justice in late 1918 after hostilities in Europe had ceased.

|

CEF Routine Order No. 815 promoted the CMPC as a "corps d'elite" intended to help commanders maintain discipline. It was to be, as much as possible, composed of soldiers returning from overseas. Battalion commanders were instructed to recommend only the "very best type of man" for police duty and APMs were instructed to exercise great care in selecting men for transfer. All candidates had to serve a month-long probationary period before being formally accepted into the corps. A CMPC Training School, commanded by Major Baron Osborne, was formed in Rockcliffe (Ottawa), Ontario, and operated from June 1918 until March 1919.

|

|

In Europe, the Corps of CMP was rapidly scaled back after the cessation of hostilities in November 1918, and by May 1919 its remaining elements were mainly located in England. By the spring of 1920, most Corps of CMP personnel had been repatriated to Canada for demobilization. An APM and MMP element were separately raised in Canada and deployed with the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force to Vladivostok, Russia in late 1918, but the entire CSEF was redeployed back home by June 1919.

In Canada, the remaining elements of the CMPC were disbanded by mid-1920 as part of the military downsizing following the war. The last major task of the CMPC was to form and operate a large "Special Guard" force to escort many thousands of repatriating Chinese Labour Corps troops (disparagingly known at the time as "coolies") who were traveling across Canada by train, from Halifax to Vancouver Island, before boarding ships for China. The CMPC Special Guard escorted about 49,000 Chinese labour troops between September 1919 and March 1920. Thus ended Canada's first foray into large-scale military policing.

|

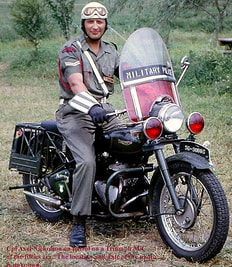

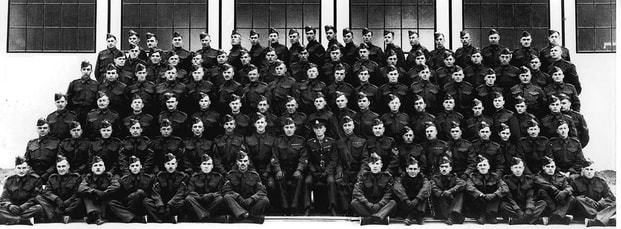

No. 1 Provost Coy (RCMP), Ottawa, Ontario, December 1939. (Photo: DND)

No. 1 Provost Coy (RCMP), Ottawa, Ontario, December 1939. (Photo: DND)

On 9 September 1939, when Canada again found itself at war with Germany, the Army's limited policing capability comprised a few Garrison Military Police at each Military District and a handful of Regimental Policemen who belonged to their Permanent Force units. Four days later, the Commissioner of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) recommended to the Minister of Justice that a "Provost" company be formed from RCMP volunteers to provide military police support for the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, the first expeditionary element to deploy overseas. The Defence Minister readily approved this offer and No. 1 Provost Company (RCMP) was quickly organized and equipped in the manner of a standard British Army Military Police Company. In early 1940, No. 2 Provost Company was raised from Canadian Army volunteers (many of whom also had civilian police experience) to support the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division. Other Provost Companies soon followed. Effective 15 June 1940,* Privy Council Order 67/3030 created the Canadian Provost Corps (CProC) into which all army provost and military police elements in Canada and oversees were amalgamated. In September 1940, Colonel Philip Augustus Puize was appointed as Provost Marshal and became the first permanent head of the CProC.

* This date has been adopted by the modern Military Police Branch as its birthday.

* This date has been adopted by the modern Military Police Branch as its birthday.

Although the CProC was considerably downsized in 1945 after the war ended, it continued to provide military policing services to the Canadian Army until the integration of the Canadian Forces in 1966. More information about CProC history can be found at the Canadian Provost Corps Association and MP Virtual Museum websites.

Royal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) Canada began operating in early 1917 as an Imperial unit (independent of local command) to help train aviators for the ongoing war in Europe. On 1 February 1918, the RFC Canada appointed an APM and assigned about 50 men to duties as policemen. They conducted patrols, monitored the discipline of airmen on leave, and escorted absentees back to their units. This reduced the workload of the CMPC in policing the increasing number of airmen in Ontario. On 1 April 1918, the RFC Canada became the Royal Air Force (RAF) Canada. That month a small guardroom was opened in Toronto, which by July had been replaced by a larger detention facility with attached barracks for the APM's staff. The first and only APM of the RFC/RAF Canada was Captain J. W. Langmuir, a Torontonian who had joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1915 as a machine gun officer before transferring to the flying corps a year later

The RAF Canada was followed by the short-lived Canadian Air Force (1920-24) and the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in 1924. However, the small size of these post-war air forces left little requirement for a full-time policing service. Instead, most security and policing duties were carried out by general duty NCOs with little specialized training under the authority of the station adjutant. This would change after the outbreak of the Second World War.

The rapidly expanding wartime RCAF quickly created a new Service Police (SP) trade. Flying Officer G. H. Jerome, formerly with the Ontario Provincial Police, was appointed as the first RCAF Provost Officer in October 1939 and posted to No. 1 Manning Depot in Toronto to supervise SP training. The first course began a month later. SP training eventually moved to RCAF Station Trenton in mid-1940, where it remained until the war's end.

In March 1940, in order to better coordinate the quickly growing number of SPs across the air force, Squadron Leader (later Group Captain) M.M. Sisley was appointed as Provost Marshal of the RCAF and authorized the form a new Guards and Discipline Branch within the Directorate of Personnel—the nucleus of which later became the Directorate of Provost and Security Services in 1941. Provost Marshal Sisley quickly selected six additional officers to act, along with F/O Jerome, as APMs at command headquarters and certain key stations. Most of these officers were veterans of the First World War, and all but one had a civilian police background. These APMs were quickly trained and operating at their new posts by June 1940. To resolve questions about the RCAF's legal authority to have made such appointments on its own, on 22 October 1940 the government passed Order-In-Council No. 528 to formally authorize the the Minister (Air) to appoint RCAF Provost Marshals and assistants.

|

From these auspicious beginnings, the wartime RCAF Provost and Security Services Branch eventually grew to about 4,000 SPs and 140 officers in Canada, and another 400 SPs and 7 officers overseas. RCAF Service Police controlled access to installations and airfields, provided internal perimeter security, conducted disciplinary patrols, carried out police investigations and ran six Command Detention Barracks. In 1942, a Special Investigation Section was established to help meet the increasing demand for specialized investigative services. Also in 1942, in response to a proposal by the Provost Marshal (Wing Commander Sisley), the RCAF Women's Division established a "Service Patrol" trade to help ensure discipline among of the growing number of airwomen across the country. The RCAF became the first service to employ women on police duties, beating the Canadian Women's Army Corps (CWAC) Provosts by one month.

|

Following the end of the Second World War, the RCAF's Service Police organization was reduced to a paltry 5 officers and 60 men. However, in the early 1950s—overseen by the renamed Directorate of Air Force Security—it rapidly re-expanded and adapted to properly police and protect an increasing number of RCAF stations and personnel in Canada and Europe as the air force grew to meet its new 'Cold War' NATO commitments.

|

A "Security Control Headquarters" was created in 1950 with three regional units to provide the RCAF with a counter-intelligence capability. This organization was later expanded and renamed the Special Investigation Bureau (and later still the Special Investigation Unit), and became responsible for sensitive security and criminal investigations. In 1951 women re-entered the RCAF, but this time, instead of being part of a separate women's division, they could join as Service Police with the same training, authority, ranks and responsibilities as their male counterparts. The RCAF Service Police trade was briefly redesignated Security Police from 1952 to 1955, after which time it was renamed again to Air Force Police (AFP) in 1955, New shield-style police badges were adopted in 1958 to replace armbands as the mark of authority for AFPs and RCAF Security Officers.

|

|

During the early 1960s, the Directorate of Air Force Security and its AFPs were assigned a huge additional responsibility for the physical security of the nuclear warheads being assigned to RCAF units in Canada and Europe (BOMARC surface-to-air missiles and GENIE air-to-air rockets for NORAD, and nuclear gravity bombs for our CF-104 strike aircraft with NATO). During this time, a robust Sentry Dog program was introduced at the RCAF bases in Germany to help protect these highly sensitive nuclear weapon systems. By 1966, a total of 812 AFPs and RCAF Security Officer were employed in direct support of nuclear security duties.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s the four-fold mission of the RCAF Security Services branch--comprising the Directorate of Air Force Security, the security staffs at each command headquarters, the regional special investigation units, and the Air Force Police sections at each station--was:

|

This Security Services branch continued to provide policing and security services to the RCAF until the integration of the Canadian Forces in 1966. More historical information about the Air Force Police can be found at the MP Virtual Museum.

Royal Canadian Navy

The ship's police system served the small RCN throughout the First World War, but was replaced shortly thereafter in 1919 (again following the RN's lead) with the introduction of a new Regulating Branch comprising Masters-at-Arms (MAAs) and Regulating Petty Officers (RPOs). Collectively, they were commonly know as Regulators. Since only a small cadre of Regulators existed during the inter-war years, disciplinary patrols on naval establishments and in adjoining towns (AKA shore patrols) often relied upon regular sailors being tasked on a rotating basis. Serious criminal matters involving navy personnel were handled by local police forces or the RCMP.

|

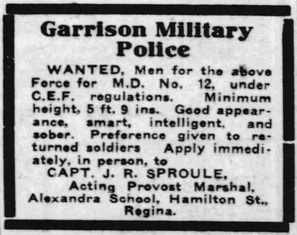

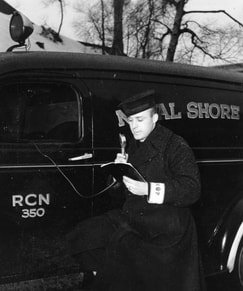

When Canada entered the Second World War the RCN began appointing Naval Provost Marshals at its larger establishments and expanded upon the pre-war system of having Regulators supervise the employment of other sailors on shore patrol duties. However, this system was found wanting as the RCN quickly grew into one of the largest navies in the world.

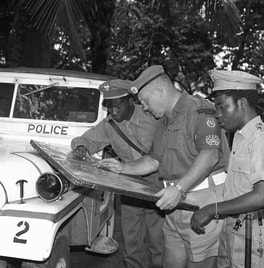

In early 1943, the RCN embarked on a campaign to recruit men for full-time shore patrol duties. Mature candidates between 30 and 45 years of age were desired, but those with previous civilian or military police experience and in good physical shape were accepted up to 50 years of age. Later that year the Naval Shore Patrol Service (NSPS) was instituted as a separate branch under a Director of Shore Patrol Services, who reported directly to the Chief of Naval Personnel. The RCN established a Shore Patrol Training School in Halifax under the command of Lieutenant-at-Arms Wilfred Pember (a former RPO and MAA who later become the RCN's first and only Lieutenant-Commander-at-Arms in 1952). Naval patrolmen with the NSPS carried out various functions including shore patrols, train patrols and security guard duties. However, serious criminal investigations on naval establishments were still conducted by civilian police.

|

|

By April 1945, the RCN's Naval Shore Patrol Service was 1600-strong and its members routinely patrolled jointly with CProC and RCAF SP personnel in large centers like Halifax and Montreal. Although shore patrol duties were only open to men, the Women's Royal Canadian Naval Service did employ a small number of Regulating Wrens to help ensure discipline within its ranks, and some of these women were later promoted to Wren Master-at-Arms positions.

At sea, RCN Regulators were employed on larger ships for discipline and policing, as well as a variety of quartermaster duties.

|

After the war, the NSPS was phased-out and the RCN returned to its old system of a small number of Regulators augmented by shore patrols landed from ships when sailors went ashore on leave. However, in 1952 the navy again saw the wisdom of a permanent shore patrol force and the Naval Shore Patrol (NSP) was established under the direction of a Naval Provost Marshal. Alas, in 1960 the RCN abolished the Regulator and Master-at-Arms ratings and merged these personnel into a new Boatswain trade (along with Quartermasters, Sailmakers and some Gunnery Instructors). This meant the regular Navy no longer had any service policing capability similar to the Army Provost or Air Force Police. However, the RCN reserve component retained its Regulating Branch ratings until early 1968. The regular RCN again reverted to a shore patrol system that used non-specialist sailors to police other sailors until 1966, when 191 navy personnel were identified to form part of the new Military Police trade during the integration of the Canadian Forces. These personnel were presumably Boatswains with previous regulating or shore patrol experience.

Canadian Forces Integration and Unification

On 26 March 1964, the Minister of National Defence tabled a "white paper" in Parliament that outlined a major restructuring of Canada’s military. The first step would include the integration of logistics, administration and personnel support services for the three armed services (RCN, Canadian Army and RCAF) and the creation of a functional command system to conduct operations. The final step, unification, occurred on 1 February 1968 when the three services were abolished and replaced by a single new service called the Canadian Armed Forces.

|

The initial step toward integrating the military police and security elements of the three armed services took effect in October 1964 with the formation of the Directorate of Security (DSecur), within the Chief of Personnel branch, at Canadian Forces Headquarters.

By April 1966, the single-service Provost Marshals and security staffs had been eliminated and new command and base security officers were appointed at the various newly-formed functional command headquarters and renamed Canadian Forces Bases (CFBs). Additionally, the various police and security investigative organization of the three services were amalgamated into a single entity called the Special Investigation Unit (SIU).

|

|

To achieve a common approach throughout the Canadian Forces, security and police functions were regrouped into three main categories:

A new Military Police trade was created to the replace the five related single- service trades, and new standards were adopted to guide the training required for all members employed in the police and security field.

|

|

In June 1966, Major General Turcot was directed to examine the role, organization and responsibilities for security in the CF and make recommendations for any revisions. At the time of his study, there existed two competing philosophies within the police, intelligence and security functional areas. The Director General Intelligence (DGI) saw a distinction between the police and security areas but a closer relationship between security and intelligence. The Chief of Personnel saw the police and security functions as complimentary. The Turcot report, released on 22 July 1966, directed that responsibility for security should be placed under the DGI.

In January 1967, the CDS directed the DGI to undertake a further analysis with a view to recommending the future management system for the intelligence, security and military police enterprises in the Canadian Forces. This study, conducted by a DGI working group, resulted in the Piquet report.

|

Security Branch: 1967 - 1999

The Piquet report, tabled on 27 March 1967, concluded that the security, intelligence, and police functions should all be managed as an integrated entity under a Director General Intelligence and Security (DGIS) within the Vice Chief of Defence Staff (VCDS) branch. Further recommendations included:

- transferring DSecur, from the Chief of Personnel, to VCDS/DGIS,

- replacing the Air Force Police School, Canadian Provost Corps School, and School of Military Intelligence with a new Canadian Forces School of Intelligence and Security (CFSIS),

- upon unification, merging all CProC officers, Canadian Intelligence Corps officers and RCAF Security officers into a new Security classification,

- retaining separate Military Police and Intelligence Operator trades for non-commissioned members, and

- grouping these two trades and one officer classification into a new security career field.

|

The recommendations of the Piquet report were approved by the CDS on 3 May 1967. The Security Branch informally came into effect on 1 February 1968 when the Canadian Forces Reorganization Act was signed into force (formalizing the unification of Canada's military forces). However, for several years the terminology was unsettled and the organization was variously referred to as the "Security Service" and "Security Services." The name was formalized as the Security Branch with the publication of Canadian Forces Administration Order 2-10, AL 35/71, on 27 August 1971.

Between 1968 and 1975, the fledgling Security Officer occupation went through several changes. It was originally planned to include five sub-occupations: Military Police, Investigation, Intelligence, Imagery Interpretation, and Interrogation. From 1971 and 1974, the new Security Services Basic Officer Course (qualification training for commissioned officers) consisted of 84 days devoted to police and security instruction, and only three days to Intelligence subjects. Further analysis in 1975 led to the adopting of two sub-classifications, each with their own unique qualification course:

|

While the two-stream officer training system worked much better than the pre-1975 approach, events would soon precipitate even further change. In 1978, the Craven Report recommended a separation of the MP/security and Intelligence functions within the unified Security Branch, and creation of two separate branches. After further studies, discussions and recommendations, DGIS concurred with the Craven Report and on 3 December 1981 the CDS directed that separate Security and Intelligence Branches be established. On 1 October 1982, the Intelligence occupations separated to form a new Intelligence Branch. From that date onward, the redesignated Canadian Forces Security Branch comprised only those personnel in the Security Officer occupation (commissioned military police officers) and the Military Police trade (non-commission members).

|

One of the most controversial and disliked aspects of unification was the adoption of rifle-green service dress uniforms (also known as "CF greens"), and accompanying "work dress" ensembles, for all personnel in the sea, land and air environments. From 1966 to 1973, there was much mixing of old and new uniforms and hat badges. However, throughout this period MPs on patrol and in the field were commonly identified by the white on black "MP" armband. A shield-style MP badge, based on the general shape of the old AFP badge, was later issued for wear with the service and work dress uniforms, as well as carriage in a special wallet for identification when wearing civilian clothes.

The much reviled green CF uniforms were replaced with three Distinctive Environmental Uniforms (DEUs) in 1986 to better align personnel with the sea, land and air environments. Because the Security Branch provided MP and security support across environmental lines, and since the Branch had been borne from the police organizations of all three former services, it chose to adopt all three DEUs. From 1986 onward, all Branch personnel were assigned an environmental affiliation and issued the corresponding uniform set. Notwithstanding, uniform assignment has no bearing on the training syllabus or ability of MP personnel to work in any of the three environments. The Branch is considered "Purple," so those members wearing naval DEU can serve in the field with MP Platoons, those in the army DEU uniform can police air bases, and those in the air DEU can provide MP support to the Navy.

|

Thunderbird Badge

|

The Thunderbird has been the symbol of Military Police in the Canadian Armed Forces for half a century.

In 1967, with integration ongoing and the unification of the three armed services into a single service looming on the horizon, an Insignia Steering Group (ISG) was formed by the Director General of Intelligence and Security (DGIS) to recommend a new badge to replace all the corps and service insignia used by previous military policing and intelligence entities.

After studying a dozen or so proposals the ISG, chaired by Major William P. Stoker (CProC), recommended the use of the aboriginal totemic Thunderbird as the symbol for the nascent Security Branch and DGIS concurred. The symbology underlying this decision was rooted in the oral histories of the Northwest Pacific Coast First Nations.

|

“The thunderbird is a mythical aboriginal spirit, probably derived from the eagle, whose name signifies the voice of thunder. It is one of the most common emblems of the Northwest Coast aboriginal tribes and is often the crowning figure on carved totem poles before the chief’s house. It is believed to be a symbol of supremacy and power in the life of the tribe. The mystique surrounding this emblem varies according to the legends of the tribe concerned. The common features of its attributes, however, concern its role as a protecting spirit, one who gives wise counsel and guards the tribe from evil and misfortune. The face on the breast symbolized dual transformation. These attributes make it an appropriate symbol for the Security Branch of the Canadian Forces. It is a bold and striking emblem, distinctive in appearance and identifiably Canadian.”

|

In choosing the Thunderbird, the fledgling Canadian Forces Security Branch would now have a symbol that:

In developing the final Thunderbird badge design for the Security Branch, staff from the Directorate of Ceremonial at National Defence Headquarters closely studied the works of two skilled artists of the Kwakiutl people: Chief Mungo Martin and Henry Hunt.

|

In 1976, the Chief of Defence Staff approved a Branch flag incorporating the Thunderbird badge. Both the badge and flag were carried over to the Military Police Branch when it was renamed in 2000.

A more detailed history of how the Thunderbird Badge came to be, including images of several early design drafts, can be found on our website at: Looking Back - The Thunderbird Badge.

Military Police Branch: 2000 - Present

|

Following recommendations made in the Dickson Report, a sweeping overhaul of the National Defence Act and Code of Service Discipline took place between 1997 and 1999 that gave new powers and responsibilities to the military police and separated the responsibilities for security and criminal investigation functions:

|

* The CFNCIU continues to be heavily staffed by MP Branch personnel in recognition of their unique investigation knowledge and skill sets.

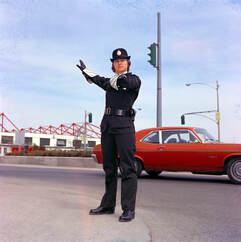

In 2001, the Military Police Operational Patrol Dress (MP OPD) was introduced to provide a common standard for domestic policing duties. It is immediately recognizable as a police uniform, while still retaining military elements. It consists of black trousers with cargo pockets, short-sleeved collared shirts for summer, long-sleeved collared shirts for winter, police shoulder patches, an insulated patrol jacket, a high-visibility waterproof jacket, soft body armour, and a modern police belt/equipment ensemble. In 2005, the red beret was authorized for wear by all trained MPs and MPOs. Prior to this, only MP Branch members assigned to the Land (Army) environment had been permitted to wear the red beret.

|

In November 2007, the CFPM assumed command of the newly created Canadian Forces Military Police Group (CF MP Gp). This formation includes the CFNIS (headquartered in Ottawa, ON), the Military Police Security Service** (also headquartered in Ottawa), the Canadian Forces Service Prison and Detention Barracks (CFB Edmonton, AB), and the Canadian Forces Military Police Academy (CFB Borden, ON). In 2011 further reforms were instituted to strengthen the military justice system, which included the CFPM being given full command of all military police personnel with law enforcement responsibilities (while still allowing local commanders to assert operational control over security functions). As a result, the CF MP Gp grew to include three environmental MP formations:

** Originally called the Military Police Security Guard Unit.

|

|

For the last 80 years, Canadian military police have been continually active throughout the world supporting Canada's military operations, including: the Second World War, Korean War, Cold War, first and second Gulf Wars, and numerous United Nations peacekeeping missions like those in Egypt, the Congo, Cyprus, the Golan Heights, and former Yugoslavia. From 2002 to 2014, they deployed in large numbers in a variety of combat support and training roles during NATO-led operations in Afghanistan and surrounding areas. Canadian military police continue to help protect 45 Canadian Embassies and High Commissions world-wide and and they routinely deploy in support of humanitarian and contingency operations around the globe.

|

|

Today, the Canadian Forces Military Police Branch comprises approximately 2,200 Regular and Reserve personnel who serve on every military base and station in Canada and on most Canadian Armed Forces operations overseas. From its humble beginnings, the MP Branch has evolved into a modern, professional police service that is highly respected within the Canadian law enforcement community and by its international military police peers.

|

On 15 June 2024 the Military Police Branch celebrated its 84th Anniversary. However, the history of military policing in Canada truly dates back to the colonial period and includes a significant, albeit short-term, surge during the First World War. Canada's Military Police members look forward to upholding a proud tradition of serving the Canadian Armed Forces at home and abroad, across the spectrum of conflict, with distinction and honour.

|

Discipline by Example: 75 Years of Military Police in Canada by Lindsay Frey, Brian Kelly and Tim Utton (Editors).

|

You can learn more about MP history between 1940 and 2015 with the book Discipline by Example: 75 Years of Military Police in Canada, published during our 75th Anniversary year.

Through official photographs and personal snapshots, Discipline by Example tells the stories of the men and women who have policed the Canadian military at home and abroad since the Second World War, and for whom the unofficial motto of the Military Police Branch — "Discipline by Example" — holds special significance. You can purchase your copy today through our Kit Shop or directly from the publisher, Blurb.

100% of all proceeds from the sale of all printed and electronic versions of this book will go to the Military Police Fund for Blind Children.

|