Looking Back: Canada's First Service Policewomen

By Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Thobo-Carlsen (Retired), CMPA Director of History & Heritage.

In 1974 women gained to right to serve in the Military Police trade of the unified Canadian Armed Forces. However, this was not the first time Canadian women had undertaken service policing functions. Women had previously served in this capacity during the Second World War and some continued to do so in two of the pre-unification armed services until around 1965.

Many thousands of men volunteered for military service after Canada entered the Second World War in September 1939, but by early 1941 it was clear there were not enough recruits to meet the increasing demands being placed upon Canada's three armed services. In April of that year representatives from the army, navy and air force met to discuss the possibility of employing women to supplement or replace men in many non-combat and medical roles. As a result, in July 1941 the Canadian Women’s Auxiliary Air Force was established and by February 1942 it had been renamed the RCAF Women's Division (WD). In August 1942 the Canadian Women's Army Corps (CWAC) was created. Finally, the navy established a similar branch in July 1942—the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS). As each of these organizations grew they recognized the need for service policing capabilities to help maintain discipline within their ranks. Although women had to a limited extent been employed in certain Canadian civilian police agencies prior to the war, they had never before served in a military or naval policing capacity before.

Royal Canadian Air Force Women's Division

|

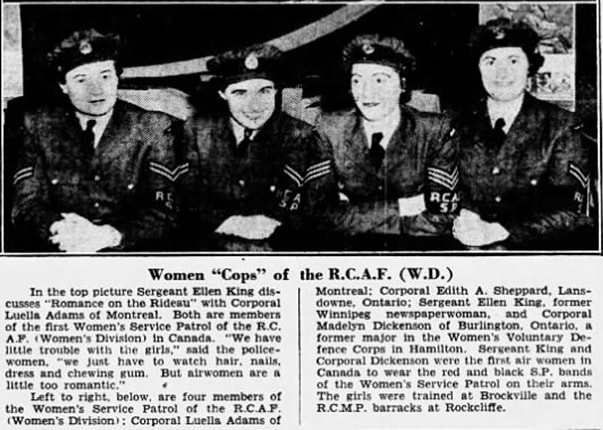

In March 1942 the RCAF WD became the first of the women's branches to authorize the creation a service policing trade, and by July the initial group of trained members began their new 'SP' duties. Although the air force recognized the need for a unique trade to help maintain discipline within its female cohort, there was resistance in some circles at RCAF headquarters for women to be called Service Police like their male counterparts. A compromise was eventually struck which saw this new capability named Service Patrol, ostensibly to project a somewhat softer image. However, period newspapers has no problem recognizing them for what they were—service policewomen.

The WD Service Patrol had an initial compliment of only 28 members, but its establishment grew much larger over time. Although these female SPs had no jurisdiction over men in the RCAF, they exercised the same legal authority and powers of arrest over airwomen that their male SP counterparts enjoyed over airmen. From April 1943 onward, Service Patrol members were also empowered to arrest servicewomen from the CWAC and WRCNS.

|

|

Service Patrol candidates needed to be between 28 to 40 years of age and a minimum height of five feet six inches. They also needed to be of good character and reliable temperament, and have at least a "high school entrance" level of education.[1] Candidates were required to undergo an intensive four-week training course which included SP organization and polices, guardhouse procedures, patrol operations (including foot, car and train patrols), laws and regulations, arrest and use-of-force, investigative procedures, report writing, giving evidence, fingerprinting and identification, first aid, unarmed self-defence (jiu-jitsu/judo) and revolver shooting.[2] Graduates of the first course were all promoted to the rank of acting Corporal (as a minimum) to establish a non-commissioned officer cadre for this new trade. However, some graduates of later courses began their wartime careers as SPs in the junior 'aircraftswoman' ranks.

Over time the number of Service Patrol positions was raised with a goal of comprising about 1% of the overall strength of the RCAF WD. Female SPs were added to the unit establishments of Air Force Headquarters, the various training command headquarters across the country, and at some RCAF stations. In addition, they were employed within the existing Service Police Command Pools where the commanding Assistant Provost Marshals has the authority to send WD SPs to whichever RCAF units and stations had a need. In November 1943 Assistant Section Officer Dorothy G. Richardson of the WD was commissioned in the Provost and Security Services Branch, becoming the first woman Deputy Assistant Provost Marshal in the RCAF. Her duties included special responsibility for the welfare and employment of service patrolwomen.[3]

|

|

Members of the Special Patrol carried out a variety of duties to help ensure discipline within the RCAF WD. This included patrolling cities and railway stations to monitor dress and deportment, scanning travel and leave passes, and generally assisting airwomen as they arrived in unfamiliar cities. Less frequently they would act as escorts for airwomen who were under arrest. The female SPs also conducted frequent train patrols to uncover absentees and quell any inappropriate behavior amongst travelling airwomen. From time to time, RCAF service patrolwomen would also accompany RCAF service policemen in car patrols as they made there rounds to check on the conduct of airmen and airwomen at amusement centers, recreational facilities and drinking establishments,

|

|

Throughout the life of the wartime Service Patrol trade, the normal duty uniform for its members consisted of the standard Women's Division tunic, skirt, peaked cap and black leather shoes worn with stockings. WD members wore the same hat badges as their male RCAF counterparts. Until 1945 the standard "RCAF SP" armband, with red lettering on black fabric, was the only unique item worn to distinguish Service Patrol tradeswoman from other WD members. Although service patrolwomen were trained to employ revolvers in emergency situations, they were not routinely armed on duty.

In February 1945 changes were made to the uniform identifiers for both male and female SPs in the RCAF. The photograph show here (right) was published in period newspaper articles to communicate these change to the general public. The caption below appeared alongside this photo in the Lethbridge Herald (Lethbridge Alberta, Saturday, 17 February 1945, page 20).

R.C.A.F. Service Police have been issued with new insignia of their trade. The new outfits for male S.P.'s and those of the W.D. S.P.'s on city and train patrols are shown [here]. The hat bands are scarlet with black lettering as are the armbands which bear in addition a gold albatross and crown. The white gloves will be worn only on special occasions. The only new addition for S.P.'s on station will be the armband. —R.C.A.F. Photo. |

Following the surrender of Germany in May 1945 and Japan in August 1945, the RCAF WD began to quickly demobilize and it was fully disbanded by the end of 1946. However, the post-war RCAF soon re-established a Woman's Division and opened the Security Police trade to women in 1951—granting them the same training, authority, ranks and responsibilities as their male counterparts.[4] This trade—which was later renamed Air Force Police—remained open to women until 1965 when Canada's military forces entered the 'integration' period that proceeded full 'unification" three years later.[5]

Canadian Women's Army Corps

|

The Canadian Army soon followed the lead of the air force, and in July 1942 approved a request by its Provost Marshal to employ CWAC servicewomen on provost duties. Initial recruiting notices mentioned an age range of 25–35 for CWAC provost candidates, but later ads upped the minimum age to 30. Some younger candidates are known to have been accepted. There appears to have been no minimum height requirement for this trade, but some ads noted candidates needed to be of "good physical build." Period newspaper articles also listed such other desirable characteristics as "suitable temperament," "intelligence," "tact and judgment," and "firmness and the ability to make quick decisions."

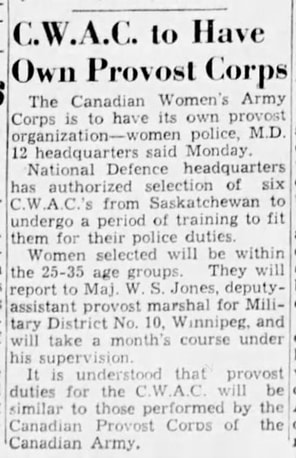

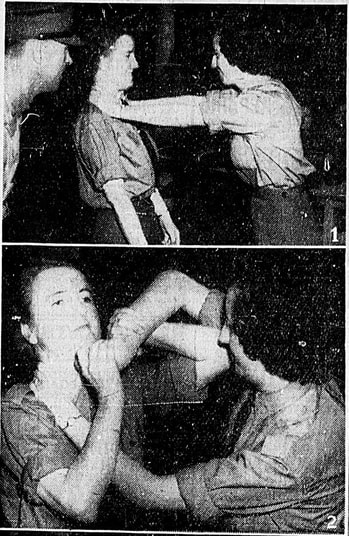

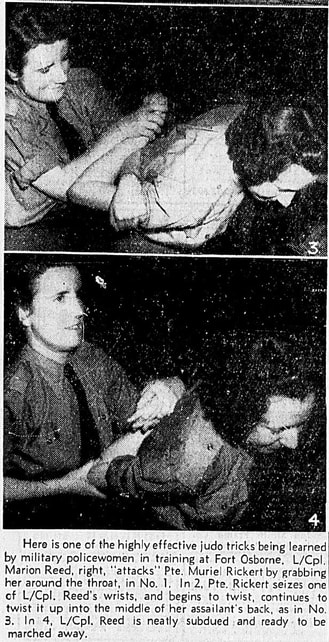

The first 72 volunteers were sent to Fort Osbourne Barrack in Winnipeg for training, with their classes beginning in mid-August 1942. Only 62 members of this initial group successfully completed the month-long course, which included drill, army organization and customs, military law, traffic control, security and safety, arrest and unarmed self-defence (based on jiu-jitsu and judo). Like their counterparts in the RCAF, CWAC provost's were trained to use of pistols but were not routinely armed. For the first two years, CWAC provost training remained decentralized and was carried out at various military districts across Canada. However, in August 1944 all such training was consolidated and moved to the main Canadian Provost Corps Training Centre—also known as A32—in Camp Borden, Ontario. A total of six 4-week CWAC provost courses were conducted in Borden until April 1945.[6]

Period newspapers gave wide coverage of the introduction of the the CWAC Provost trade, and some of these articles provide us with rare photographic glimpses of the army's new military policewomen.

|

|

CWAC Provosts wore the standard uniform of the women's corps. Winter dress consisted of an olive drab tunic, skirt and brimmed cap, worn with brown leather shoes and stockings. The tunic epaulets, neck ties and sewn on badges were in a contrasting dark brown colour. The summer dress tunics, skirts and caps were made of a lightweight fabric in tan/khaki colour.

CWAC provosts wore "MP" armbands similar to those used by their male counterparts in the Canadian Provost Corps (CProC), as well as red lanyards. One Ottawa newspaper article from December 1942 described the CWAC armbands as having red lettering on a dark blue fabric background, whereas the standard CProC armband employed a black cloth background.[7] Another news article from Montreal in February 1944 (above, far right) described the CWAC 'brassards' as having black lettering on a red background, so it appears several varieties were used at different times and locations across the country.

|

These military policewomen patrolled city streets, railways stations and other areas frequented by CWAC personnel to ensure they conducted themselves in proper military fashion. They were sometimes required to apprehend absentees and escort them back to their units, and much less frequently to carry out arrests for more serious offences. For the most part, they acted as an invaluable resource to shepherd young servicewomen and tactfully correct any unmilitary dress or behavior issues before any of these became a major problem.

CWAC provost has the authority to arrest servicewomen from either the WRCNS and the RCAF WD if required. However, they did not have the general authority to arrest male soldiers, sailors or airmen. Below is a reprint of Canadian Army Routine Order 4368, which provides an overview of how these military policewomen were employed and administered in the 1944 timeframe.[8]

4368 – C.W.A.C. PROVOST

R.O. 2443 is hereby cancelled and the following substituted:

1. For the information of all concerned, selected personnel of the CWAC are being posted for duty with the Canadian Provost Corps as Provost personnel.

2. C.W.A.C. Other Rank personnel will be posted to the C.Pro.C. Company with which they are to be employed and will be shown as attached back to the appropriate C.W.A.C. Administrative Unit for such purposes local conditions may warrant. The extent of such attachment will be at the discretion of the district Officers Commanding concerned. C.W.A.C. Provost will not, however, be accommodated in the same quarters as other C.W.A.C. personnel. If no separate accommodation is available, they will be placed on subsistence.

3.(a) The duties of C.W.A.C. Provost will, insofar as the exigencies of the Service permit, be restricted to C.W.A.C. personnel and they will generally exercise all the powers, rights, privileges and duties of soldiers detailed to perform the function of Military Police. Insofar as the Provost Marshal may direct, C.W.A.C. Provost as Service Police may exercise the rights and duties outlined in R.O. 3252. C.W.A.C. Provost will NOT, however, perform any of the duties outlined in R.O. 3773 in as much as the rights and privileges conferred therein are confined exclusively to members of the C.Pro.C.

(b) C.W.A.C. Provost will, while on duty, be identified by the Arm Band worn by personnel of the C.Pro.C

(H.Q. 54-27-111-111)

The CWAC Provost trade reached its peak toward the end of 1944 when around 450–500 servicewomen were employed in this role. Most served only in Canada, but some female provosts also served abroad. Following the end of hostilities, the army's women corps was fully demobilized by September 1946. The Canadian Army re-established the CAWC in March 1951, but women were never employed in the regular component of the Canadian Provost Corps. However, beginning in 1961 a small number of CWAC servicewomen in the reserve component (militia) were trained to carry out provost duties. It was not until the mid-1970s—after the unification of the Canadian Armed Forces—that women would contribute to policing in the regular force of the army.

Women's Royal Canadian Naval Service

|

When the WRCNS was formed in June 1942 its members became known as 'Wrens,' a term that was adopted from the Royal Navy in Britain where the women's naval branch went by the acronym WRNS— or Wrens when pronounced phonetically. A wren (bird) was also featured at the top of the WRCNS branch crest.

Canada's navy had traditionally taken a different approach from the other services when it came to policing its own. The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) had long viewed discipline as a job primarily for the chain of command of each individual ship or shore-based unit, and it was not until early 1943 that the RCN created a dedicated Naval Shore Patrol Service to carry out duties ashore similar to those undertaken by the Canadian Provost Corps and the RCAF Service Police. However, the RCN did have a history of employing Regulating Branch members as disciplinarians, including afloat on its larger ships, and some of their 'regulating' duties were of a policing nature.

|

|

It is not yet clear when the WRCNS regulating (Ship's Police) trade was first established, and not much is currently known about its training regimen or the overall number of Wrens employed on regulating duties. However, it was certainly a smaller number than in the other two services. All regulating trades training is believed to have been carried out at the main Wren Training Center at HMCS Conestoga in Galt, Ontario.

The earliest mention this author has found of a Wren Regulating Petty Officer (RPO) is from a newspaper article published on 27 April 1943 (photo, right). In this article, RPO Sally Farlinger's duties were described as follows:

Regulating Petty Officer Farlinger would not stay long in this role however, as she was commissioned in the rank of probationary sub-lieutenant in July 1943. Farlinger was replaced at the naval HQ in Vancouver by RPO Dorothy Benson (photo, below right).

Documentation uncovered so far suggests that the regulating component of the WRCNS had a broad range of disciplinary and related personnel management duties, many of which fell outside the activity sets of the RCAF Service Patrol and CWAC Provost trades. As such, the Wren regulator's role included a greater emphasis on guiding the daily activities of Wrens to help instill good discipline. However the Wren regulators—particularly those holding RPO or Master-at-Arms (MAA) rank—did play a central role in the daily defaulters parades to help their commanding officers address alleged breaches of military regulations.

A WRCNS recruiting ad from a period newspaper had only these few words to say about the desirable characteristics of women seeking to carry out regulating duties:

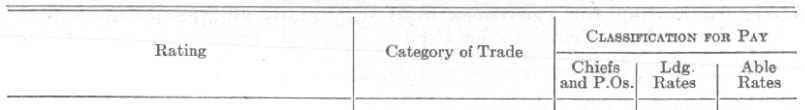

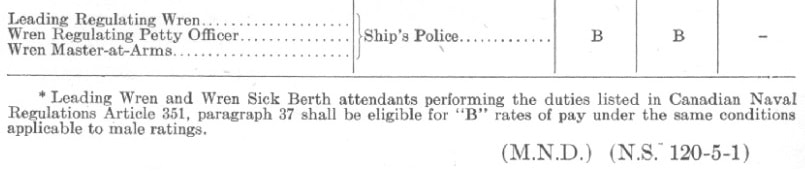

An amendment to the WRCNS Regulations in December 1944, reproduced in part below, shows how the Wren "Ship's Police" trade was set up at that time. Other documents from earlier in 1944 suggest that Wren regulators had previously also been employed at the 'able' rating (rank)—similar to today's Sailor 2nd Class rank. However, by December of that year these lower ranks had been eliminated. All other Wren trades, except for plotters, retained their able ratings—demonstrating that Ship's Police tradeswomen required slightly elevated experience levels and rank due to the nature of their disciplinary duties.

|

|

|

The standard Wren winter dress uniform consisted of a dark blue double-breasted jacket and matching skirt, white shirt, black tie, black leather shoes and stockings. Petty officers and chiefs wore a 'tricorne' hat and the lower ratings wore a 'beret,' which was really a feminine version of the traditional sailor's cap. The later cap replaced an earlier wide-brimmed hat that proved unsuitable for uniform wear in windy conditions. The summer uniform of the WRCNS was based upon a lightweight tunic/skirt combination in a medium blue shade.

Unlike in the RCAF WD SPs and CWAC provosts, identifying armbands were not worn by Wrens in the Ship's Police trade. Instead, Wren regulators wore an embroidered crown centered on the right sleeve of their tunic as a distinguishing badge, just like RPOs wore in the RCN. Wren MAAs (who were chief petty officers) also followed the RCN tradition by wearing a badge with a crown surrounded by laurel leaves on each lapel of their tunics. Although these regulating and MAA badges look very similar to the rank badges worn by some petty officers and chief petty officers in today's RCN, during the Second World War these badges did not denote rank and were worn only by Regulating Branch members in the RCN and Ship's Police members in the WRCNS.

Over time, at least 12 women in the WRCNS Ship's Police trade were promoted to the MAA rating. At least five former Wren regulators became commissioned officers. One of these was Sub-Lieutenant Mary Johnston, who received her commission in September 1943. After joining the Wrens, Johnson was quickly promoted to Petty Officer and posted at HMCS Stadacona (Halifax, NS) where she first served as an RPO and then as the MAA. Below is an excerpt from a newspaper article that also carried the photo of her (right):

While most Wren regulators served only in Canada, some were posted to Newfoundland (which was not part of Canada until 1949) as well as oversees. For example, Master-at-Arms Phyllis Sanderson was stationed in Scotland later in the war and awarded the British Empire Medal in June 1945 for her meritorious service.

|

|

The WRCNS was fully disbanded by August 1946. Although the RCN did reintroduce Wrens in some reserve trades beginning in 1951, and some women joined the RCN's permanent component in 1954, they were not employed in regulating or shore patrol duties. Women would not resume any policing duties at naval establishments until the military police trade was finally opened to them in the mid-1970s.

EpilogueDuring the Second World War some 21,624 women served in the CWAC, another 17,038 in the RCAF WD, and a further 6,783 in the WRCNS. With so many women in uniform for the very first time, many of whom had never been away from home before, the service police trades in the three women's branches proved essential in shepherding those servicewomen who sometimes strayed from the military's many rules and regulations. Although these service policewomen occasionally had to act as enforcers, more often that not they were able to act in a guiding manner to either prevent misbehavior or correct minor infractions before they got out of hand. These wartime servicewomen helped break down traditional barriers and paved the way for women to become equal partners in the Canadian Armed Forces' military police occupation three decades later.

|

----------

Notes:

1. Ronald J. Donovan and David V. McElrea, A History of the Royal Canadian Air Force Police and Security Services (Renfrew ON: General Store Publishing House, 2008), 40

2. Ibid, Appendix I, 222 and DHH 74-14, The History of the A.M.P. Division, Chapter VIII - The Directorate of Provost and Security Services, 139.

3. Donovan and McElrea, 40. Assistant Section Officer was the WD rank equivalent to Pilot Officer in the wartime RCAF, and is comparable to Second Lieutenant in today's Canadian Armed Forces.

4. "Women RCAF Police," Vancouver Sun, Vancouver, British Columbia, Saturday 14 September 1951, 35.

5. The RCAF Service Police trade was first renamed Security Police in 1952 and then Air Force Police in 1955.

6. Andrew R. Ritchie, Watchdog: A History of the Canadian Provost Corps (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995), 123 and "Provost Course Opens for C.W.A.C's," Calgary Herald (Calgary, Alberta), Friday 11 August 1944, 6.

7. "Ottawa Girl in Military Police Learns Use of Pistol and Jujitsu," The Ottawa Journal, Ottawa, Ontario, Tuesday 1 December 1942, 7.

8. As reprinted in Richie, Watchdog, 124–125.

9. "Teacher from East Oversees WRENS Here," Vancouver Sun, Vancouver, British Columbia, Tuesday 27 April 1943, 6.

10. "Noted Skating Star Now in Wren Uniform," Vancouver Sun, Vancouver, British Columbia, Friday 30 July 1943, 11.

11. "Montrealer 'Up from Lower deck' now Wren Unit Officer at Kings," The Gazette, Montreal, Quebec, Tuesday 28 September 1943, 4.

Notes:

1. Ronald J. Donovan and David V. McElrea, A History of the Royal Canadian Air Force Police and Security Services (Renfrew ON: General Store Publishing House, 2008), 40

2. Ibid, Appendix I, 222 and DHH 74-14, The History of the A.M.P. Division, Chapter VIII - The Directorate of Provost and Security Services, 139.

3. Donovan and McElrea, 40. Assistant Section Officer was the WD rank equivalent to Pilot Officer in the wartime RCAF, and is comparable to Second Lieutenant in today's Canadian Armed Forces.

4. "Women RCAF Police," Vancouver Sun, Vancouver, British Columbia, Saturday 14 September 1951, 35.

5. The RCAF Service Police trade was first renamed Security Police in 1952 and then Air Force Police in 1955.

6. Andrew R. Ritchie, Watchdog: A History of the Canadian Provost Corps (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995), 123 and "Provost Course Opens for C.W.A.C's," Calgary Herald (Calgary, Alberta), Friday 11 August 1944, 6.

7. "Ottawa Girl in Military Police Learns Use of Pistol and Jujitsu," The Ottawa Journal, Ottawa, Ontario, Tuesday 1 December 1942, 7.

8. As reprinted in Richie, Watchdog, 124–125.

9. "Teacher from East Oversees WRENS Here," Vancouver Sun, Vancouver, British Columbia, Tuesday 27 April 1943, 6.

10. "Noted Skating Star Now in Wren Uniform," Vancouver Sun, Vancouver, British Columbia, Friday 30 July 1943, 11.

11. "Montrealer 'Up from Lower deck' now Wren Unit Officer at Kings," The Gazette, Montreal, Quebec, Tuesday 28 September 1943, 4.