Looking Back: RCAF Police in The Roundel

The Roundel was the monthly news magazine of the pre-unification Royal Canadian Air Force. A total of 175 issues were published over the course of 17 volumes, from November 1948 until June 1965. Two articles showcased the Air Force Police organization, one published in 1956 and the other in 1960. Both articles, reproduced below, provide an interesting glimpse into the history and culture of the RCAF's Directorate of Air Force Security and it's Air Force Police Branch during the early Cold War period.[1]

The R.C.A.F.'s POLICE FORCE

Prepared by the Air Force Police Branch,

Directorate of Air Force Security.

Directorate of Air Force Security.

INTRODUCTION

Although our Air Force Police is one of the youngest military police forces in the world, with a history of only sixteen years, it is nevertheless rich in experience gathered during the Second World War and during the uneasy peace that has followed. Furthermore, its roots are grounded in 300 years of military police tradition.

It was in 1643 that King Charles the First of England issued the following instruction: "The Provost must have a horse allowed him and some soldiers to attend him, and all the rest commanded to obey and assist, or else the service will suffer, for he is but one man and must correct many, and therefore he cannot be beloved. And he must be riding from one garrison to another, to see the soldiers do no outrage nor scathe the country."

In point of fact, the Provost Marshal's organization, although not as the strictly military body we know today, goes back 900 years to the Norman Conquest, when the first Provost Marshal accompanied William the Conqueror to England. From that time until the 17th century, the Provost held powers of life and death over soldiers and civilians alike. According to a 15th century historian, it was not lawful for the men of the Provost Marshal to go about at any time without their halters, withes, and strangling-cords.

Since the 17th century, when the Provost Marshal's organization became a military body, its role has changed to the protection of the Serviceman and his equipment in order to preserve his efficiency as a fighting man.

HISTORY OF THE AIR FORCE POLICE

Before the outbreak of war in 1939, the R.C.A.F. had no police organization, and such police duties as were necessary were carried out by General Duties airmen without special training. The number of personnel employed in this capacity was small, and in June 1939 the total establishment for R.C.A.F. Station Trenton was one corporal and three aircraftmen.

In July 1939, thought was given to the creation of a trade of Service Police. After successful completion of a suitable course, personnel were to qualify for the trade of Service Police with a "C" grouping. Nothing was done, however, until October of that year, when the first provost officer was appointed. The first police course began at Toronto on the 2 December 1939, and classes were held in the "Bull Ring" of the Canadian National Exhibition which doubtless seemed an appropriate place in which to conduct a police course!

The first Provost Marshal was appointed in March 1940. Authorized to form, within the Directorate of Personnel, a Guards and Discipline Branch, he selected seven assistants who, with commissioned ranks, would represent him in the Commands. Of these seven, six came directly into the Service from civil police agencies.

In late 1941, the Guards and Discipline Branch reached sufficient size to warrant the formation of a separate directorate; and the Directorate of Provost and Security Services, embracing the Service Police and Security Guard Branches, was formed. A Special Investigation Section was created within the Directorate, with the responsibility of conducting all criminal investigations in the R.C.A.F. It is interesting to note that many of the personnel of this Special Investigation Section went on after the war to distinguish themselves in senior police positions in towns and cities across Canada.

After the war the Service Police dwindled from a peak of nearly 5000 officers and men to some 5 officers and 60 airmen. The outbreak of the Korean War, however, together with Canada's responsibilities under N.A.T.O., brought about a general expansion in the R.C.A.F. and a consequent increase in the Police Branch. In November 1950 the Directorate of Air Force Security was formed and made responsible for the prevention of espionage, sabotage, and subversion, for the maintenance of law and order, and for ground defense training of all personnel in the Air Force. Ground Defense became a separate directorate in 1953.

FUNCTIONS

Today the mission of the Air Force Police is:

- the protection of classified information,

- the protection of R.C.A.F. material against sabotage,

- the protection of R.C.A.F. civilian and service personnel against subversion, and

- the prevention, detection, and investigation of crime.

|

The primary purpose of the Air Force is, of course, to carry out air operations. When, therefore, we consider the disastrous effects that espionage, sabotage, and subversion can have on air operations, the importance of protection from these forms of covert attack can be readily understood. Espionage can rob us of our advances in military science, disclose our weaknesses and strengths, and give away our methods of defence to a potential enemy. Sabotage can destroy our aircraft and installations for defence before they can be used. Subversion can undermine confidence and morale, and reduce efficiency and the will to resist. Thus, the Air Force police must necessarily give first priority to that part of its mission which aims at countering these threats.

|

(Let us remind the reader here that no security measures and no efforts of the Air Force Police will provide effective security unless they receive the complete support and co-operation of everyone concerned with their success. Security against covert attack is not just the responsibility of commanders and police personnel; it is the individual responsibility of all Air Force personnel, both Service and civilian. Intelligent co-operation with the Air Force Police—a co-operation which stems from an awareness of the danger to be combatted—is essential in ensuring that the air operations of the R.C.A.F. are not hampered or their effectiveness nullified at a critical time.)

Although priority must be given to the prevention of espionage, sabotage, and subversion, the importance of the prevention of crime in the Service must not be forgotten. Crime, too, can impair the efficiency of the force. The loss to the Air Force, resulting from crime, can be serious far beyond the gravity of the individual offences. A carelessly dropped cigarette can cause the destruction of a costly and important installation, the theft of equipment can hinder an air operation or endanger life. Crime is contagious; it grows if not suppressed in time. It is the duty of the Air Force Police to see that it is stamped out wherever it appears.

ORGANIZATION

To accomplish the vital security mission assigned to it, the Air Force Police is organized as follows:

A.F.H.Q

Responsible to the Director of Air Force Security are the Security Branch (for security of information, personnel, and materiel) and the Police Branch (for prevention, investigation, and detection crime).

Commands, Groups, and Divisions

The Staff Officer Security is responsible to the A.O.C. for security and police functions within the Command.

Units

The unit Air Force Police are responsible to the C.O. for the security and policing of the unit.

Special Investigation Bureau

Responsible to A.F.H.Q., the Special Investigation Bureau is established on a regional basis in Europe and in all provinces of Canada except Newfoundland.

RECRUITING

Men and women apply to join the Air Force Police for many different reasons; but, whatever their reasons, Air Force policemen and policewomen need intelligence, patience, strength of character, and sometimes bravery. They must also have a calm and judicious approach to their calling.

The Air Force Police contains in its ranks men and women drawn from many sources. Its personnel include ex-members of the R.C.M.P. and of the provincial, municipal and railway police forces of Canada. There are members of the London Metropolitan Police, and many British city and county police forces are represented. A number have served with the British military police and intelligence organizations, and the British colonial police forces have contributed ex-members from Palestine, Malaya, Hong Kong, Singapore, Shanghai, and Rhodesia. The largest number, however, have come into the force as inexperienced personnel and have been trained by the R.C.A.F.

In late 1951, women were reintroduced into the trade of Air Force Police. Policewomen are established on all units having a complement of more than 25 airwomen and at each Special Investigation Unit. They are to be found at radar stations in Canada and at R.C.A.F. Wings overseas. They receive the same training as men, even to the manly (or womanly) art of self-defence. Although they fulfill a normal police function, they are primarily concerned with airwomen.

TRAINING

All members of the Air Force Police are required to attend the Air Force Police training course at R.C.A.F. Station Aylmer, Ontario, regardless of previous experience. In addition to this basic course, Air Force Police are accepted for training by various police schools in Canada, the United States, and Great Britain. Training is also provided in special fields, such as identification and interrogation, and selected personnel are given training in arson investigation within the R.C.A.F. and at Purdue University in the United States. Air Force police have attended courses at the Canadian School of Military Intelligence, Camp Borden, and the Canadian Provost Corps School, Camp Shilo. Air Force Police officers and N.C.O.s are regularly included in the R.C.M.P. College courses at Regina and Rockcliffe, and in the Maritime Police School at Halifax.

DUTIES AT UNITS

The primary function of the Air Force police on units is the protection of life and property, and to this end all efforts are bent. Whether conducting security checks to ensure that all classified matter is adequately protected, or quelling a disturbance or directing traffic, the purpose of their duties is the same: the protection of serving personnel and public property. Air Force police maintain a 24-hour watch on the station, and many of their duties are performed when the rest of the personnel of the unit are enjoying themselves in recreation or are asleep in bed. During weekends or holidays you will always find an Air Force policeman on duty. They maintain patrols in all weather, by day and by night; for there is no real substitute for the man on patrol, who, as he goes quietly on his rounds, is quick to notice any unusual circumstance.

|

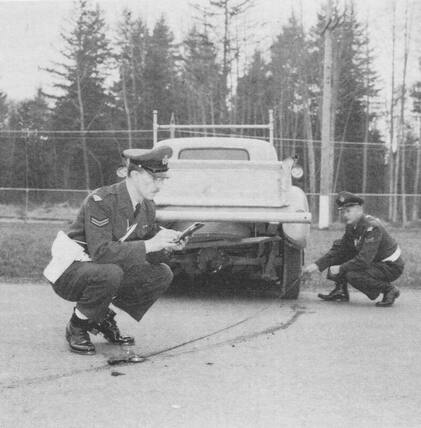

Air Force police handle the finger-printing and photographing of personnel for identification purposes, they take care of the custody and escort of Service prisoners, they supervise the control of entry to the unit, and they investigate Service and criminal offences. They must often spend long hours in the investigation of crime, frequently working overtime. They are called upon to handle all disturbances on the unit—and sometimes off the unit in adjacent towns, when R.C.A.F. personnel are involved. Although these tasks are usually performed quietly and without difficulty, there have been occasions when Air Force policemen have been confronted with great personal danger, and they must always be alert to protect themselves and others in the vicinity.

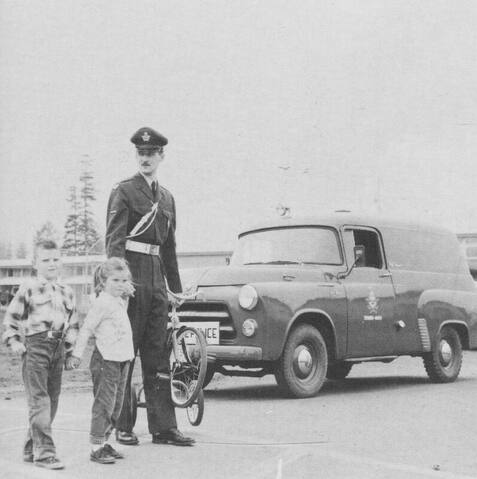

The Air Force police are ready at all times to assist the airmen of the unit. To this end the guardhouse is a general information centre for all newcomers. The police run a lost-and-found bureau on each unit, and recover articles lost on trains and other forms of public transport. It is a rare day indeed when the unit police are not called upon to help someone who needs the benefit of their knowledge and contacts. Not long ago an airman was beaten and robbed in a city near his unit. His appeal for help to his unit brought prompt action. The Air Force police, with the assistance of the civil police, were able to bring about the arrest of the assailant and recover a portion of the stolen money for the airman.

|

No policeman, no matter how minor his task, can carry out his duties efficiently without giving his whole-hearted support to the policies he must execute. But his efficiency is also predicated to a large extent upon the support he receives from the rank and file of airmen, among whom he must move and work. The police owe a duty to the airmen, but, conversely, the airmen owe a great deal of responsibility to the police. Law observance is far better than law enforcement. Law observance is the exercise of a desire and willingness from within to comply with established rules; law enforcement is the exercise of a power from without—and generally against the will of the individual.

SPECIAL INVESTIGATION BUREAU

The Special Investigation Bureau is established on a regional basis with units in Edmonton, Toronto, Montreal, and Metz (France), and with detachments of these units in Vancouver, Whitehorse, Calgary, Saskatoon, Winnipeg, London, Trenton, North Bay, Ottawa, and Halifax. Each unit is commanded by an Air Force Police officer; each detachment is in charge of a senior N.C.O. Their duties consists [sic] of the background enquiries necessary for security clearances and the investigation of crime. Some of their work takes them far off the beaten track into northern Manitoba and Saskatchewan and the interior of British Columbia, where overnight accommodation is a sleeping-bag thrown on the ground beside the car and breakfast is served to the aroma of wood-smoke.

The Special Investigation Bureau is manned in such a way that well trained men are available for every phase of investigative work. They are always at the call of any commanding officer to conduct or assist in investigations which he considers beyond the capabilities of his own police resources. Since this organization is established on a regional basis in Canada and Europe, its men are quickly available to most units, and can, in most instances, be on hand to take over an investigation in a few hours from the time they are called.

RELATIONS WITH OTHER POLICE FORCES

Air Force police deal constantly with the public, and the rest of the Air Force is often judged by the appearance and bearing that these men present. They are in constant touch with other military and civil police agencies. In Europe excellent relations exist between the Air Force Police and the French gendarmerie, the German security police, and the British county police. Patrols in Metz are conducted by the Air Force Police and the U.S.A.F. Police jointly; in Rabat, by the Air Force Police and the Moroccan Police.

The civil police, by making their facilities available, greatly assist the Air Force police in the performance of their duties. The work of the latter would be difficult indeed without the constant co-operation and assistance afforded by the civil police and by other military police agencies. The training given by these agencies, the assistance of their experts, together with the assistance provided by the facilities of their laboratories, are a constant support. On the other hand, the Air Force police stand ready at all times to assist these agencies by passing on information, gathered in the course of their duties, respecting personnel who are, or may be, involved in criminal activities; and, when requested, they will assist in locating potential witnesses or suspects from among Service personnel.

CONCLUSION

The maintenance of law and order, the prevention of crime, and the apprehension of criminals are the functions of civil police forces. To carry out this task they have special powers given to them by law. Like their civil police counterparts, the Air Force police represent, within the Air Force, all the majesty of the law, and are vested by law with special powers to carry out their duty of the maintenance of law and order. Yet, unlike the majority of civil police, they have, in addition to and transcending this duty, the duty of protecting the Air Force from espionage, sabotage, and subversion. That they are capable of adequately fulfilling all their functions, there is no doubt. But, as has already been said and cannot be too often repeated, they cannot do it alone. They are merely a part of the great team which works to keep the R.C.A.F.'s aircraft effectively in the air, and the essence of all teamwork is co-operation between all the components engaged in it.

|

Views expressed in “The Roundel" upon controversial subjects are the views of the writers expressing them. They do not necessarily reflect the official opinions of the Royal Canadian Air Force. |

A Day With the Air Force Police

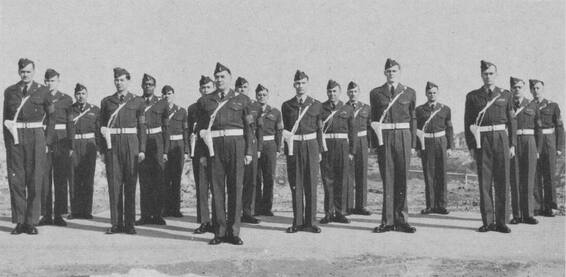

An air force unit is a community and, like all communities, requires protection. This vital requirement is in the hands of specialists—the air force police.

|

The primary function of the air force police is the protection of life and property and to this end all their efforts are bent. Whether conducting security checks to ensure that classified matter is adequately protected, quelling a disturbance or directing traffic, the purpose of their duties is the same.

Air force police maintain a 24-hour watch on stations and many of their duties are performed when the rest of a unit's personnel are in bed asleep. During weekends or holidays you will always find an air force policeman on duty. They maintain patrols in all weather, by day and night, for there is no real substitute for the patrol who, as he goes quietly on his rounds, is quick to notice any unusual circumstance.

The air force personnel in the accompanying pictures are typical of the more than 900 men and women who make the business of our protection their life's work.

|

View the May 1956 article in it's original format (scanned .pdf):

|

| |||||

|

| |||||

View the October 1960 article in it's original format (scanned .pdf):

|

| |||||

----------

Note:

1. As the 50-year Crown Copyright period (covering Canadian government publications) has expired for all editions of The Roundel, the information and photographs reproduced here are considered to be in the public domain.

Note:

1. As the 50-year Crown Copyright period (covering Canadian government publications) has expired for all editions of The Roundel, the information and photographs reproduced here are considered to be in the public domain.