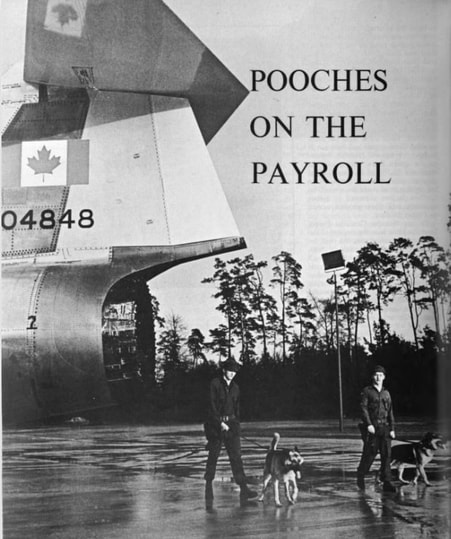

Looking Back: Pooches on the Payroll (Sentry Dogs)

In the early 1960s, the Canadian government agreed to a nuclear strike role for some of its CF-104 Starfighter squadrons assigned to NATO duty in West Germany. The RCAF went on to fulfill this mission with thermonuclear gravity bombs provided by the United States Air Force (USAF).

This new role had a profound effect on the RCAF's security and police organization, which was tasked to implement strict nuclear security measures to NATO and USAF standards. Air Force Police (AFP) manning quickly increased from 60 to over 190 personnel at each of the two RCAF nuclear-capable bases: 3 (Fighter) Wing, Zweibrücken and 4 (Fighter) Wing, Baden-Soellingen. To ensure adequate security during darkness and periods of reduced visibility, the RCAF established a Sentry Dog Program based upon the USAF model.

In 1969, following the unification of the Canadian Armed Forces the year before, Canada vacated the Zweibrücken base as an austerity measure. Those air units that were to remain in Germany were consolidated at Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Lahr and CFB Baden-Soellingen. CFB Lahr then became a nuclear-capable base for one year with its own supporting Sentry Dog Section.

Another impact of unification was that the AFP dog handlers were subsumed into the newly created Military Police (MP) trade, but otherwise the sentry dog teams continued their nuclear weapon security duties as before.

In the September 1970, an article was published in Sentinel (the magazine of Canadian Forces) about the sentry dog teams at Lahr and Baden-Soellingen. This article—which was written only 16 months before the sentry dog program came to a close after Canada ended its nuclear air strike role—is reprinted below in it's entirety.

Sentinel

Volume 6, Number 8, September 1970

The following article appeared on pages 6-9 of this edition:

Volume 6, Number 8, September 1970

The following article appeared on pages 6-9 of this edition:

by Captain Tom CoughlinThe rain pelted down cutting visibility to a few yards as a Canadian Forces military policeman and his German Shepherd started their patrol. Except for the occasional flash of lightning the restricted area of No. I Wing at Lahr, Germany, was in total darkness. Suddenly the dog stiffened. The corporal neither saw nor heard a thing but the dog persisted. With mounting excitement the dog strained at his leash as he concentrated on some unseen objective. The corporal was forced into a fast walk by the agitated shepherd. Suddenly the policeman released the straining mass of muscle and the dog disappeared into the night. In a few seconds screams of fear and pain pierced the darkness. The corporal broke into a run as he headed for the source of the commotion. Moments later he arrived on the spot and there, lying on the ground, was a man securely held down by the vice-like grip of dog teeth. The shepherd had intercepted an intruder.

This anecdote is unreal, because it has not happened. But it is not unrealistic because it could happen.

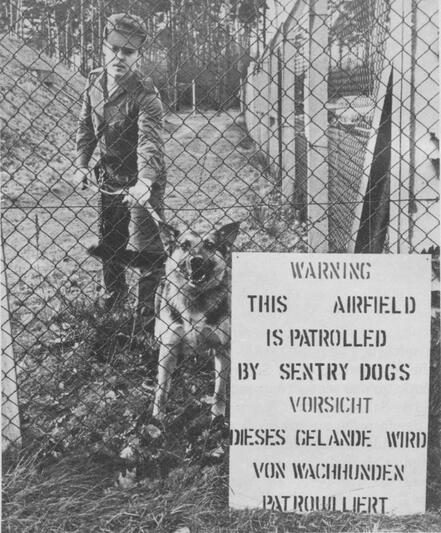

The Canadian Armed Forces NATO-assigned Air Group operates in Germany and, like all military establishments [in Europe], there are restricted areas that the military police operate a sentry dog section.

|

|

The use of sentry dogs, in what was then the RCAF, began in April 1963 when 17 Canadian military policemen were sent to the US Air Force Sentry Dog School at Wiesbaden, Germany for a six-week course. Upon graduation from the course, the 17 dog handlers plus 17 German shepherds, valued at $350 each, were sent to RCAF Station Zweibrucken, Germany, to take up sentry duties. They quickly proved their worth.

Today there are Canadian sentry dogs and handlers at Lahr and Baden-Soellingen, Germany. The dog handlers are all military policemen and all are volunteers for this specialized phase of police work. They also must be very dedicated people. Since the dog handlers are always on duty at night they are seldom able to be present at social functions such as parties and dances which are well attended by servicemen in other lines of work.

For the dog handlers and their dogs, training never ceases. One day a week training exercises are held to hone a fine edge onto an already keen man/dog teamwork. During these exercises the shepherds demonstrate that their sense of smell has a range of 250 yards; their sense of hearing is 20 times greater than a human's and their eyesight is 10 times greater. Even at night, in absolute darkness, the dogs can see an incredible distance, provided their quarry is moving. If the object of their search remains stationary, however, then the dogs must fall back on their sense of hearing or smell.

The most dramatic part of the weekly training exercise is the attack phase. For this demonstration a man, wearing a padded suit for protection, hides behind a small wooden barricade. Then a trainer starts across an enclosure with his dog on a leash. The trainer will criss-cross the field or walk on a straight course in any direction except towards the concealed man. At some point along the way, depending on the strength and direction of the wind, the dog will pick up the scent. There is an immediate transformation. The shepherd's ears arch forward like radar antennae and he strides with more purpose. As he becomes more confident that he is onto something he digs in with his powerful hind legs forcing his handler to move faster. Then two things happen almost simultaneously. The trainer will release the dog and the man will break and run from his place of concealment. He hasn't a chance.

|

|

|

The dog blurs across the intervening distance and sinks his teeth into the padded outfit. The sheer strength of the dog plus the fury of his attack will flatten most men. In any event, the policeman runs to the scene and orders the dog to cease the attack. The shepherd's task is not finished. The trainer will move him back 10 paces and order him to sit down. Then the policeman will go through the motions of frisking the "suspect". For training purposes, the captured man will suddenly lunge out at the policeman. The reaction is immediate. The dog hurtles himself at the man hitting him with huge paws which resemble soup plates. Then the dog grabs a mouthful of padded sleeve and subdues the suspect. Again the policeman intervenes and orders the dog off. The demonstration is over and, once more, a dog handler and his dog have given vivid proof that they can cope with anyone who has ideas about intruding onto a Canadian military airbase in Europe.

In spite of the fact that sentry dogs are trained to attack people, they are not considered to be vicious animals. Sergeant N. E. Mercer, who is in charge of the sentry dog section at Lahr, states emphatically that vicious dogs would not be acceptable to the section because they would be uncontrollable. Sentry dogs are aggressive not vicious. A vicious dog is one which is apt to bite anyone at anytime out sheer malice whereas an aggressive dog will only attack when he is ordered to do so. This subtle difference might not be appreciated by an intruder as a bundle of fur bore[s] down on him but the difference is a matter of great importance to the safety of the dog handlers.

|

|

Although the man/dog teams are quite capable of handling guard duties, they are not alone. Each dog handler carries a walkie-talkie while on patrol, so help is close at hand. If a dog picks up a scent or hears something he wants to investigate, his handler will call the Central Security Control on his radio and ask for a Sabotage Alert Team (SAT) to stand by in case he needs them. Within minutes patrol cars loaded with military policemen can be on the spot to provide reinforcement.

Occasionally a dog will "alert" on someone who has authority to be in the area. For example, an aircraft mechanic could be working at night when a dog is on patrol. In such cases the dog handler will allow his dog approach the airman close enough to get a good sniff. The dog will remember that particular scent and will not go on alert if he detects the same scent again. Sentry dogs also remember their handlers for a long time.

In 1964 Corporal Vern Majury and his dog, Rolf, worked together at Zweibrucken, Germany, until the corporal was posted home to Canada in 1966 at the end of his tour of duty. In 1968 Corporal Majury was sent back overseas to serve at Baden-Soellingen. One day he decided to go to his old unit at Zweibrucken. While there be made a side trip to the kennels to see how Rolf was getting along. In spite of the two-year absence, the corporal was immediately recognized by the dog which greeted him with much enthusiasm.

Canadian security personnel consider that a man dog combination is equivalent to three men on patrol. As a result, there is a saving in manpower and in money by using sentry dogs for guard duties. There is also greater peace of mind for the men on lonely patrols knowing that they have a formidable ally by their side. Barbed wire fences, radio communications and patrol cars notwithstanding, man's best friend still finds a vital role to fill in helping to guard Canadian military bases overseas.

|

A .pdf version of the original Sentinel edition containing this article can be found on the Hathi Trust Digital Library website (external link) at: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112071911066 |

----------

Note: The article reproduced above was originally published in Sentinel, Volume 6, Number 8, September 1970, pp. 6-9, for which DND/CAF holds the copyright. This reproduction complies with the non-commercial use provisions published at: www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/corporate/intellectual-property/crown-copyright.html

Note: The article reproduced above was originally published in Sentinel, Volume 6, Number 8, September 1970, pp. 6-9, for which DND/CAF holds the copyright. This reproduction complies with the non-commercial use provisions published at: www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/corporate/intellectual-property/crown-copyright.html