Looking Back: Black Military Police Pioneers

By Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Thobo-Carlsen (Retired), Director of History & Heritage, and Major Mathias Joost (Retired) .

As Canada's Military Police Branch continues to foster and improve its inclusiveness, it is important to remember that it was not always so. It is therefore appropriate to look back on some Black military police trailblazers. Recent research has identified two men of colour who served in military policing roles in Canada during the First World War period, and another who provided provost support overseas. Most of what is know about these soldiers has been gleaned from their military personnel files and genealogical records. Furthermore, several unidentified black men are known to have served in a regimental police capacity with No. 2 Construction Battalion as far back as 1916. Future research may uncover even earlier soldiers of colour who helped pave the way to a more racially and ethnically diverse body of military police in Canada.

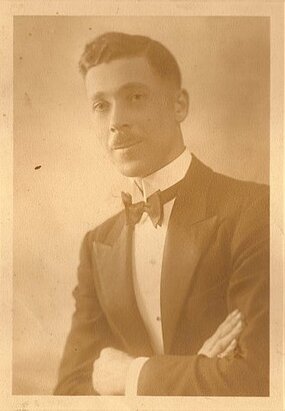

Lance Corporal Albert John Ryan — Canada's First Black Military Police Member?

As men across Canada flocked to enlist at the start of the First World War, Black Canadians were disadvantaged. Commanding officers had the right to determine who could enlist in their battalions, with the result that in many places Black men were rejected because of the colour of their skin. This was not the case with all units.

Albert John Ryan was born on 12 March 1884 in Fredericton, New Brunswick, the third son of Daniel and Catherine Jane (née Costello). He was born into a large family, having two older brothers and one older sister, and four younger brothers and two younger sisters. In 1901 Ryan was a clerk, and he would later became a chef.

On 6 March 1915 Ryan enlisted in the Composite Battalion in Fredericton. The battalion was formed in 1914 as a unit of the Canadian Militia (and not the Canadian Expeditionary Force) to replace Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR) personnel who had been deployed to Bermuda. The Composite Battalion recruited from the three Maritime provinces and was headquartered at Wellington Barracks[1] in Halifax, Nova Scotia. It shared these quarters with No. 6 Special Service Company, No. 6 Casualty Company and a small complement of remaining RCR members. The 800 men of the battalion guarded strategic points around the Halifax military dockyard, along with troops from artillery batteries and infantry regiments who guarded others sites. The locations that the Composite Battalion specifically guarded included the dry dock, the North ordnance yard and some of the piers.

As Ryan's military duties took him to Halifax, his wife Annie moved there and they lived together on Doyle Street. For over two years his main routine consisted of guard duty in Halifax; however, the Military Service Act (MSA) was to change the situation for him. The MSA allowed conscription. After the the Act became law on 29 August 1917, all men between ages 20 and 45 had to register and have a physical examination performed. Conscription was unpopular, which meant that many men did not register. As civilian police did not have the personnel in most cities across Canada to check men on the street to confirm whether or not they had registered, it was largely left to military police to do so. This was the case in Halifax.

To help enforce the MSA, military police at the various military districts across Canada were reorganized into numbered detachments of a new formation of the Canadian Expeditionary Force called the "Military Police (C.E.F.)." These detachments were authorized on 15 September 1917, and Captain Edward James Mooney—the acting Assistant Provost Marshal for Military District No. 6 (Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island)— commenced recruiting for No. 6 Detachment, Military Police (C.E.F.) on 1 October 1917. One of the 17 men enlisted that day was Albert Ryan. Twelve of these men had previously served in the Composite Battalion, and five with the 94th Regiment.

At 5' 2” (157 cms) and 109 pounds (50 kgs) Ryan was quite small compared to the others who enlisted. The medical officer noted his "poor physique" and judged him to be unfit for overseas service. Instead, he was assigned "Category C1" status which only allowed him to serve in Canada. For Captain Mooney, perhaps Ryan's size was less important than the fact that he was Black. It is quite likely that he was selected with the assumption that he would have an easier time visiting the Black areas of Halifax, such as 'Africville,' to watch for potential non-registrants.

Although we don't know what exactly Ryan did, it was clear that he had some leadership abilities. On 19 November he was made an acting sergeant—only the second person in the detachment to be promoted to that rank. But, this rank was not to remain for long. The military police detachments had been formed quickly, so as they developed and did their work an establishment review was undertaken by Militia Headquarters. As a result, the establishment of No. 6 Detachment was revised and Ryan's position was downgraded on 8 February 1918 to acting corporal while he himself became a substantive lance corporal. For most of other members of the detachment the establishment adjustment meant a promotion, although for some it resulted in a rank reduction.

A big interruption in the daily routine of No. 6 Detachment happened on 6 December 1917 with the Halifax Explosion, when the S.S. Mont Blanc—laden with explosives—collided with the S.S. Imo. The resulting explosion killed an estimated 2,000 people, injured more than 9,000 and destroyed large parts of the city. All of the military units in Halifax suffered casualties. Available military personnel were rushed to the scene— first to remove and evacuate the wounded and to help fight fires, and then to prepare shelters, transport and feed the homeless. The Military Police Detachment was involved in all of this as well as helping civil authorities police the city and prevent looting.

All this may have been too much for Ryan, whose release medical noted that he suffered from nervousness, which also afflicted his brothers and sisters, and apparently began after a trip to Boston in 1907. His superiors decided that it would be best for him to transferred to another unit. In April 1918, the 6th Canadian Garrison Regiment was formed in Halifax from the local Composite Battalion, as were similar regiments in other military districts. Ryan was transferred to 6th Canadian Garrison Regiment on 21 May 1918. Although we don't know what Ryan's exact duties were, as a lance corporal he would most likely have been supervising a small section of troops as they guarded facilities around Halifax.

Because of his anxiety, Lance Corporal Ryan was ultimately released from the CEF on 24 December 1918 on the grounds that he was unable to render efficient service. He was not the only one of the original 17 members of the No. 6 Military Police Detachment to be medically released. Four others were also released for this reason, three of them before Ryan.

Service life had to have agreed with him to some extent as he left the service at a more normal weight of 120 pounds. More importantly, his character and conduct were noted as being very good. For a Black man to be placed in a leadership position showed not only that his abilities were recognized but that Captain Mooney was without prejudice, unlike many other White officers in Canada and especially in the Halifax area. Having been able to serve in the Composite Battalion and in the Military Police Detachment, Ryan was able to demonstrate that Black men were just as capable as any others and helped lead the way for others to follow.

After the war, Albert and Annie remained in Halifax and he continued to work as a chef. Unfortunately Albert Ryan did not live long after the war. He died at sea in 1923 leaving behind his wife and four daughters.

Lance Corporal Robert James Bowen — Military Police Special Guard

Robert James Bowen is the only other Black man currently known to the authors as having served in a national-level military police role in Canada during the First World War. His employment within the Canadian Military Police Corps was pioneering, but also laced with a certain bitter irony.

Bowen was born on 31 December 1897 in Georgetown, British Guyana, in South America. He was the second child of Robert Ernest Bowen and Frances Veronica Bowen (née O’Neil). He also had an older half-brother from his mother’s previous marriage. His father was originally from Barbados, as was his maternal grandmother.

Bowen’s maternal grandfather had fought for the Union side during the United States' civil war and his grandmother immigrated to Canada (settling in Halifax, Nova Scotia) soon after his grandfather died from injuries sustained during that conflict. His grandmother’s decision to make a new life in Canada likely drove Robert and his older sister Florence to follow suit. His parents, however, continued to live in Guyana for the rest of their lives.

On 6 October 1917, Bowen enlisted in the Active Militia for service with the Royal Canadian Garrison Artillery (RCGA) in Halifax and was assigned regimental number 1274093. An enlistment document shows his civilian employment as “clerking.” Bowen was described as being 5’10” (178 cm), 146 lbs (66 kg) and of average physical development. He was assigned an “A2” medical category meaning he was considered fit for general service. In July 1918, Bowen was converted from the Active Militia to the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), but he remained with the garrison artillery. A notation in a re-enlistment document from October 1918 shows he had applied to serve in the 219th Highland Battalion but was rejected for medical reasons (hernia and eyesight)—although racial prejudice may also have played a role in his being denied an opportunity to join that unit. Notwithstanding, by November 1918 his medical category had been lowered to “C1” meaning that he was unsuitable for front-line service but still able to stay on as a Gunner with the garrison artillery until being demobilized on 18 February 1919.

It is unclear what, if any, civilian employment Bowen found after his demobilization, but he seized the opportunity to re-enlist in the fall of 1919 for special service with the Canadian Military Police Corps (CMPC). Established on 1 April 1918, the CMPC was the final evolution of military policing in Canada during the First World War. The CMPC was the direct successor of the Military Police (C.E.F) organization, which itself had been created in September 1917 to amalgamate the various military police elements at each of the Military Districts across Canada.

The CMPC was responsible to conduct military police duties across the country under the overall coordination of the “Provost Marshal for the Dominion of Canada,” Colonel Gilbert Godson-Godson. In addition to garrison policing, CMPC detachments were heavily involved in tracking down and arresting those who failed to register for conscription under the 1917 Military Service Act and rounding up deserters. However, as post-war demobilization progressed the CMPA was handed one final task—operating a “Special Guard” force to escort Chinese Labour Corps troops across Canada. These Chinese troops, disparagingly referred to at the time as “coolies,” arrived at the port of Halifax from Europe and were transported by train and ferry to Vancouver Island, where they boarded ships bound for their homeland. The government of the day, largely in line with public sentiment, decided these Chinese troops—who had aided the allied war effort overseas for years under trying condition—needed to be closely guarded during their journeys across Canada to prevent any from trying to remain in Canada illegally. The CMPC Special Guard escorted around 49,000 Chinese Labour Corps troops in total between September 1919 and March 1920.

On 28 October 1919, Robert James Bowen enlisted in the Special Guard of the CMPC where he was assigned the new regimental number 2779956 and quickly promoted to lance corporal. For the next five months, until his final demobilization on 8 April 1920 (at age 22 and 5 months), his duties would likely have consisted of riding trains across the country and acting as an armed “escort” for these repatriating Chinese labour troops. It is hard to escape the bitter irony of the situation for Bowen. On the one hand, he was as a rare member of a visible minority group welcomed into the CMPC at time when the number of White applicants to choose from was large. On the other hand, he was employed in a program specifically designed to guard against the possibility that persons from another visible minority group would attempt to take up residence in Canada. By today’s standards, the racist overtones of Special Guard program are clear.

|

Little is known about Bowen’s life after the war. The home address listed in his final pay certificate was 215 Creighton Street in Halifax, the same address where his maternal grandmother and sister are also known to have resided. He was married to Mable Jean Hartley of Lockeport, NS on 30 September 1920 and they had two children, Madeleine and Merrill. Mable died in 1933 at age 33, and in 1957 Bowen was remarried to Olivia “Leigh” Lawrence of New Glasgow, NS. They are not known to have had any children together. His 1957 marriage certificate shows that he was employed as a railway porter with the Canadian National Railway Company (CN). Olivia also worked for CN. Lance Corporal Robert James Bowen passed away in Halifax, NS on 30 May 1982 at age 84. He is buried at Fairview Lawn Cemetery in Halifax (6B. Lot 218).

It appears that Bowen was proud of his service in the CMPC even though it was of relatively short duration. The headstone at his gravesite is engraved with his CMPC regimental number rather than his earlier RCGA number, and the supplementary stone placed on his grave reads:

ROBERT J. BOWEN

LANCE CORPORAL C.M.P.C. C.E.F. 30 MAY 1982 AGE 84 |

Corporal Joseph Montague Post, MM — Cyclist Employed on Provost Duties

No records have yet been uncovered to suggest that any Black men were directly employed on military police duties with the CEF overseas. However, one soldier of colour is known to have been employed occasionally on provost support duties in France.

Joseph Montague Post was born on 23 May 1898 in Ottawa, Ontario. The 1901 census lists his father William as being Black and his mother Bridget as being White. Therefore, the Canadian government at the time listed him as being Black. Post enlisted in the CEF on 22 September 1914 under the alias of "James Post" and with a false birthdate of 22 May 1895. He was actually only 16 when he became a soldier. Joseph Montague's younger brother was named James and born on 22 May 1899, suggesting that the former may have used a doctored version of his brother's birth certificate when he attested.[2]

In any event, Post was given regimental number 26588 and initially assigned to the 14th Battalion (3rd Brigade). He set sail for Europe with his unit on 3 October 1914. In May 1915, he was transferred to the Canadian Reserve Cyclist Company and by August of that year was serving in the field with the 1st Canadian Division Cyclist Company[3]. Youthful exuberance may explain several disciplinary occurrences recorded in his military file, including a drunkenness incident that earned him 15 days of "Field Punishments No. 1"[4] at the Divisional Provost Prison in January 1916. Notwithstanding, Post was later attached to the Canadian Corps Assistant Provost Marshal (APM) as well as the 2nd Canadian Division APM on several occasions for provost support duties. Cyclist units were frequently required to detach personnel to assist the full-time military police elements with traffic control (TC) and Prisoner of War (PW) escorting and guarding, typically for periods ranging from several days to several weeks. Post's service file shows that he was attached to these APMs for TC and PW duties on at least four occasions between June 1916 and October 1917. On 11 November 1917, shortly after his last such attachment at the 2nd Canadian Division PW Cage, Post was promoted to Lance Corporal and from that time onward he maintained a clean disciplinary record. Perhaps the time spent working under the APMs had a positive influence on his overall outlook as soldier. Post is known to have participated in the Battle of Vimy Ridge, was wounded in action in March 1918, promoted to corporal in August 1918, and later awarded the Military Medal (MM) for bravery.

While Joseph Montague Post was employed only sporadically and for relatively short periods in support of provost tasks, his overall wartime contribution as a rare person of colour in a combatant unit remains significant and he helped blaze a trail for others to follow.

Regimental Military Police — No. 2 Construction Battalion

Reflecting the ingrained racism present in Canada at the time, many men of colour were turned away from joining combat units by local recruiters. However, efforts by black community leaders eventually paved the way for Canada's Department of Militia and National Defence to authorize the formation of No. 2 Construction Battalion in early July 1916. This non-combat unit composed of coloured men would eventually deploy overseas where its members provided important construction and labor support to military operations.

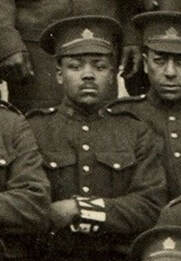

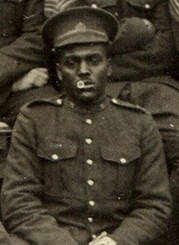

Several unit photographs have recently been found showing that select member of No. 2 Construction Battalion were employed in regimental police roles. However, to date, no information has been uncovered to identify these particulator black regimental policemen or the specific details of their employment in that capacity.

Two soldiers shown in the photograph above are wearing MP armlets. During the 1914-16 timeframe, such armlets were commonly worn in Canada by soldiers who were involved in what we now refer to as regimental policing—helping to enforce discipline within a specific unit only. Later in the war, these were generally replaced with RP (Regimental Police) or RMP (Regimental Military Police) armlets to avoid confusion with the garrison, camp or district Military Police that had a wider jurisdiction over soldiers. Therefore, the photo below is curious since it shows a member of No. 2 construction battalion (inset) wearing an armlet with either CMP (Camp Military Police) or GMP (Garrison Military Police). This suggests that some members of No. 2 Construction Battalion may have been employed within such larger MP organizations, at least on a temporary basis, as far back as 1916.

Co-author Mathias Joost

Major Joost retired from the Canadian Armed Forces in 2021 after more than 31 years of service in the regular and reserve components. He initially joined the regular force in 1985 as a naval officer, but later reclassified to Military Police Officer. After eventually transferring to the primary reserves and switching to the air environment, Major Joost spent 18 years at the Directorate of History and Heritage as the officer in charge of the Operational Records Section (including war diaries for current operations). As a sideline to his military duties, Mathias has been researching visible minorities in the military, especially Black soldiers, going back to the New France era. He has written and given presentations on the subject and is currently completing two books on Black soldiers in the Canadian military from the New France period up to the First World War.

----------

Notes:

1. The Wellington Barracks are located in the Stadacona section of present day Canadian Forces Base Halifax.

2. Corporal James A. Post (Regimental No. 144214) was the younger brother of Joseph Montague Post. James also joined the CEF as an underage soldier by misrepresenting his birth date during attestation. He apparently made a good soldier since he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for gallantry (while attacking an enemy 'pill box' machine gun emplacement) and held acting Sergeant rank for a short period while serving with the 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles—all by the age of 18. However, he was transferred out of this combat unit in May 1918 once it was discovered that he was not yet 19. James A. Post later joined the RCAF during the Second World War.

3. The Canadian Army employed independent Cyclist Companies in each Division until May 1916 when they were formed into the Canadian Corps Cyclist Battalion. The cyclists were essentially bicycle-mounted infantry, but could also be used in quasi-cavalry roles like scouting, intelligence gathering and dispatch riding. Given their inherent mobility, the cyclists were also in high demand by the Assistant Provost Marshals to augment their Military Mounted Police personnel for traffic control and prisoner of war escort duties during major combat operations.

4. Field Punishment No. 1 was a common form of disciplinary punishment during the First World War, having been introduced into the British Army in 1891 upon the abolition of flogging. Men undergoing F.P. No. 1 were placed in restraints and attached to a fixed object like a wagon wheel or fence post for up to two hours per day. It was often carried out at field punishment camps set up for this purpose behind the front lines, but when unit were on the move they would usually administer F.P. No. 1 to their own soldiers under sentence.

Notes:

1. The Wellington Barracks are located in the Stadacona section of present day Canadian Forces Base Halifax.

2. Corporal James A. Post (Regimental No. 144214) was the younger brother of Joseph Montague Post. James also joined the CEF as an underage soldier by misrepresenting his birth date during attestation. He apparently made a good soldier since he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for gallantry (while attacking an enemy 'pill box' machine gun emplacement) and held acting Sergeant rank for a short period while serving with the 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles—all by the age of 18. However, he was transferred out of this combat unit in May 1918 once it was discovered that he was not yet 19. James A. Post later joined the RCAF during the Second World War.

3. The Canadian Army employed independent Cyclist Companies in each Division until May 1916 when they were formed into the Canadian Corps Cyclist Battalion. The cyclists were essentially bicycle-mounted infantry, but could also be used in quasi-cavalry roles like scouting, intelligence gathering and dispatch riding. Given their inherent mobility, the cyclists were also in high demand by the Assistant Provost Marshals to augment their Military Mounted Police personnel for traffic control and prisoner of war escort duties during major combat operations.

4. Field Punishment No. 1 was a common form of disciplinary punishment during the First World War, having been introduced into the British Army in 1891 upon the abolition of flogging. Men undergoing F.P. No. 1 were placed in restraints and attached to a fixed object like a wagon wheel or fence post for up to two hours per day. It was often carried out at field punishment camps set up for this purpose behind the front lines, but when unit were on the move they would usually administer F.P. No. 1 to their own soldiers under sentence.